© Jeffrey Robinson 2005, 2025

The pen lived in the top drawer of my grandmother's dresser, and although I saw it regularly — because she kept butterscotch in there, too — I never really paid attention to it. But that was before some nameless bureaucrat working in some anonymous office in the New York State Department of Education issued an edict that, inadvertently, changed my life.

All high school students in the state were then required to take a series of three-hour exams in an array of subjects — freshman algebra, sophomore Spanish, senior history — that were known as the Regents Exams.

The mother of all Regents was eleventh-grade English. That's because, in addition to a slew of unfathomable multiple choice questions – “What characteristic does Charles Dickens share with Willa Cather? a) Anti-religious symbolism; b) Historical inaccuracy; c) Political incorrectness; d) none of the above" — there was the much dreaded, heavily weighted, mother of all essays.

“In 750 words, compare and discuss religious symbolism, historical accuracy and political incorrectness in the works of Charles Dickens and Willa Cather and show how they relate to Herman Melville.”

Huh?

Enter here that nameless bureaucrat from that anonymous office in Albany who not only took it upon himself to decide this would be the single most important essay we would ever write in high school he dictated that it had to be written with a fountain pen.

His decision never made a lot of sense to me. It couldn't be that he had an innate distaste for ten-cent BICs, as Monsieur Bic hadn't yet invented them. Or that some kids had shiny ballpoints with Parker or Sheaffer written on the clip, while most of us had mangy imitations with names like Long Beach Sunoco or Dino's Pizza on the barrel which, frankly, suited us just fine.

Fountain pens were awkward, leaky and scratchy. They also required a bottle of blue ink that could spill and invariably did; a blotter that smudged instead of blotted; and a lot of Kleenex, because no matter how careful you were, you and the blotter always wound up covered in blue ink.

Still, the fountain-penned essay was the law, and there was no way around it. So the rich kids showed up with fancy Parker 51s and really neat Sheaffer Snorkels while the poor kids showed up with no-names in Day-Glo colors, that only sometimes worked but had very chewable blind caps.

I opted for my grandpa's Parker.

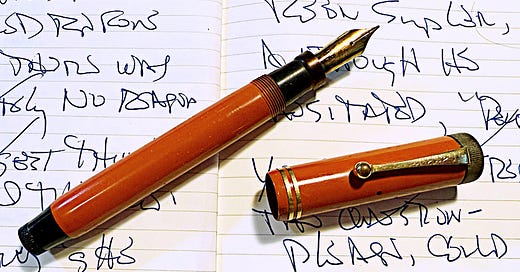

His 1928 “Big Red Duofold” with a large gold nib was more orange than red. It featured the remarkable “Lucky Curve” feeder, which changed George Parker’s fortune when he invented it at the end of the 19th century, and might have been the most expensive fountain pen on the market in those days. I later learned that Parker created it specifically to be a premium priced pen which, he hoped, would capture the spirit of the Roaring Twenties. But none of that mattered to me at the time. What mattered was that it filled easily, wrote smoothly, and I liked how it weighed big in my hand.

I have no recollection of the essay question, but while I sat there staring at the blank paper, needing to come up with 750 words about something I almost certainly knew nothing about, just holding that pen gave me the confidence to believe that, with patience, the words would flow.

And when they did, it was special. I wasn't simply moving a pen across paper, I was taking part in the act of writing. There was a direct connection between the thoughts in my head and the large gold nib.

Perhaps this is what musicians discover when they play a great violin for the first time. Suddenly, the music sounds different. It plays differently. It becomes an extension of them and, ultimately, the two of them become the music.

That's what was happening now with grandpa’s Parker. And when you're 16 and when you know that you want to be a writer and when you discover that you and a pen can be one and the same — for me, suddenly, writing was very different.

I passed the Regents and returned the pen to my grandmother, and it lived in her top drawer long after the butterscotch ran out. I finished high school and finished college and went off to war, and at the end of 1970, I moved to France to be the writer I knew I could be when I was 16.

I pounded out newspaper features and magazine articles and short stories on a big, old and clunky 1944 Royal typewriter. Trademarked “Touch Control” with no fewer than 12 listed patents, it weighed a ton. I had to punch the green keys vertically down, and every now and then, they would break, and when that happened, I'd have to stop writing and spend the morning soldering the keys back together.

Over the course of a dozen years in France, that old Royal and I published more than 600 features and articles and short stories around the world.

I still own it, and admit that I very occasionally put in a sheet of paper and type something, just to remind the machine how much I have loved it. It lives on a shelf less than an arms-length away from my main desk, on purpose, so I can smile at it and sometimes whisper to it, to remind us both of a gentler time.

During those years I was writing in France, my grandmother passed away, and what little she had was divided up between her four daughters and two granddaughters.

That's when I remembered the pen.

I wrote my mother and asked her where it was. She wrote back that she didn't know, but promised to look for it. When it turned out that one of my aunts had it, I sent her a perfect eleventh-grade-English-Regents declarative sentence: "It's mine!"

She gave it up without a fight. Which I acknowledge was a very decent thing for her to do. After all, this was also her father’s pen. But I’m sure it didn’t hurt that all my aunts, and all my cousins, too, have generally regarded me as being the crazy one in the family. And it was obvious that I really wanted that pen and really intended on having it.

Unfortunately, the years had not been kind to it. The cap no longer fit snugly; the filler stuck, and the bladder was dried out. So I did some research and decided that the only man I could trust to fix it was Ivan Mason, the founder of a small business called Penfriend in London.

I rang him from France, and when he agreed to take a look at it, my grandpa's pen and I headed for England.

Ivan's workshop was on the second floor of a dingy old building in a grimy part of town, not far from The Angel tube station. A candle burned constantly on his small, cluttered workbench. Already much older than my grandpa's Parker, Ivan had a gentle smile and warm eyes, and when he took the pen from me with his permanently ink-stained blue fingers, he studied it reverently for many minutes before reassuring me that everything would be fine. That the patient would live.

He told me I could pick it up in a few days.

I told him I would be happy to wait.

He looked at me with some suspicion, as if to say, don't you trust me with this?

I explained, "I want to watch you work on it. I want you to tell me about it."

And there I sat for the next several hours, in the company of a man who dearly loved fountain pens, as the candle burned down and he brought my grandpa's Parker back to life.

We spoke about that pen, and other pens, and all the pens he'd ever seen. And long after he was finished with the cap and the filler and the bladder, I was still there listening to him. It was more than just a writerly thing to do. I don't think Ivan charged me £10 for the work. I owe him so much more, just for the conversation.

And all these years later, using my grandpa's Parker to write this about him now, seems only fitting.

For many people, a fountain pen is a rite of passage — a gift for a special occasion, or a birthday or a graduation — a manageable step into the grown-up world of style, design and sophistication. Later, there may be watches, wine, carpets, paintings, cars and exotic lovers, hotel suites in mysteriously romantic cities where you tell someone, for the first time and outside in the rain, “I love you.”

But that first fountain pen is a luxury that befits youth.

For me at 16, already starting to write, that first fountain pen made me feel like a writer.

I have now owned my grandpa's Parker longer than he did, longer too than my grandmother did after him. I confess that, in weaker moments, I have amassed 30 or 40 other pens. My wife is aghast, although my kids – who are both talented and successful writers - are amused, especially when I hand over one of my pens and say, "Here, use this, it’s you.”

And, now, they have owned some of my pens longer than I owned them.

None of my pens are ultra-rare. None are priceless. But then, mine is not a collection of pens. I have simply amassed an assortment of writer's tools - mostly Parkers like Victories, Challengers, 51s and a couple more Duofolds - plus a bunch of Montblancs, big heavy Montblancs and now and then a big Cross, all of which happen to be of a certain age.

These are not pens I keep in a case to look at. These are pens for those moments when a computer is too mechanical and remote. These are pens for taking notes and struggling with quarrelsome paragraphs and crossing out and rewriting and scribbling in margins.

And then there is my grandpa's Parker.

That's the one what I turn to when all else fails.

It still weighs big in my hand and effortlessly connects to my brain. It's an old pal who tells me the truth. It's a partner who won't allow me to fool myself. It’s a grandpa's knee where a wondrous little kid can feel safe and hear a story.

It's the pen that makes me feel like a writer. It's the pen that gives me the confidence to know that, with patience, the words will flow.

*****

Thank you so much for sharing this story! My dad was a "penist" and he taught me to love the flow of a fountain pen.

I used my Grandmother's 1928 Sheaffer Vintage White Dot Balance Carmine Red Fountain Pen to study for my PhD comps and dissertation prep in History. I loved the mini-ness, it felt so perfect when writing. I recently brought her to Laywine's to repair the bladder.

Thank you! My heart is filled with quiet joy for you.

I had a dear friend, now no longer with us who was gifted a fountain pen by his father. They were poor and lived on the wrong side of the tracks, literally if you know Winnipeg. Before opening, his Dad said: 'this could make you a million dollars.' It never did, but I always appreciated his beauifulo prose written on that pen.